On the Fourth of July in 1912, George Mullin became the first Detroit Tigers pitcher to throw a no-hitter. Guiding him from behind the plate that day at Navin Field was a durable catcher named Oscar Stanage.

Spencer Turnbull threw the eighth no-hitter in Detroit Tigers history on May 18, 2021. Eric Haase was his catcher that evening in Seattle. Turnbull became the sixth Detroiter to twirl a no-no, while Haase became the eighth different Tiger to catch one. They were the latest pair of battery mates to travel down a path in franchise history that was first carved out by hurler George Mullin and backstop Oscar Stanage in 1912.

Of the two, Mullin is likely a more familiar name than Stanage. Mullin’s 209 victories in a Tigers uniform are second only to Hooks Dauss’ 223, but nobody pitched more innings (3,394) or completed more games (336) for Detroit than Mullin. He still ranks in the Tigers’ top ten in the categories of shutouts (2nd), starts (3rd), ERA (6th), strikeouts (7th), and bWAR for pitchers (9th).

Stanage caught 1,072 games for the Tigers. Only Bill Freehan (1,581) did it more. Lance Parrish (1,039) probably would have passed Stanage in 1986 if back problems hadn’t prematurely ended what turned out to be his final season with Detroit. No other catcher has reached 1,000 games with the team. Playing that much in a rougher and more rugged era of baseball took a physical toll. The caption underneath a 1962 Detroit Free Press photo of an elderly Stanage pointed out that “his gnarled hands are that of an old-time catcher”.

After a one-game cameo with the Cincinnati Reds in 1906, Stanage resurfaced in the majors with the Tigers in 1909. The rookie catcher started two games in the World Series that fall. In Game 4, his two-run single in the bottom of the second inning set the tone for a 5-0 Tigers triumph over the Pittsburgh Pirates.

Stanage shared time behind the plate with the more experienced Charley “Boss” Schmidt during his first two seasons and took over the role full-time in 1911. The increase in playing time resulted in 221 assists that year, but also 41 errors. Both are still single-season records for a Tigers catcher. They’re also American League records. In his ’62 interview with Lyall Smith of the Free Press, Stanage ‘snorted’ at the latter record:

"“That’s only because of those blankety-blank official scorers. Most of those errors were charged to me on throws to catch guys trying to steal bases. Everybody ran like mad those days…If my infielders hadn’t dropped so many of my throws, I’d have had a lot more assists and a lot less errors.”"

By the end of 1912, Stanage had earned the respect of the men who worked behind the plate with him. In a post-season poll of American League umpires, the Tiger was rated as the best catcher in the league. One of the era’s sportswriters, Charles A. Hughes, offered an explanation. He wrote,

"That may surprise many fans, but the umpires back their selection with good reasoning. They point to Stanage as an almost perfect receiver, a deadly thrower, close observer of batsmen’s weakness, and the equal of (Bill) Carrigan of the champion Bostons in outguessing the opposition when the hit-and-run play is to be attempted."

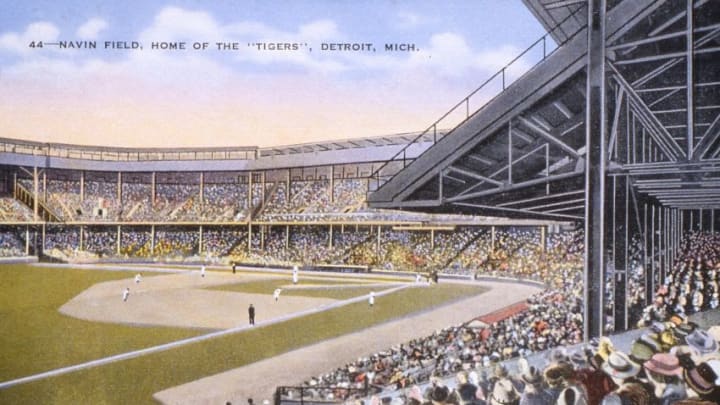

The 1912 season began with the excitement of a brand new ballpark in Detroit. The address stayed the same, but Navin Field replaced Bennett Park. The Tigers christened their new home with an 11-inning, 6-5 win over the Cleveland Naps on April 20. Both Stanage and Mullin went the distance in that one.

The duo came close to authoring a no-hitter together against the Washington Senators on May 21. Mullin gave up only a pair of hits and outdueled future Hall of Famer Walter Johnson (who doubled). The Tigers’ 2-0 victory in the nation’s capital was notable for another reason. It was the first game back for Detroit’s regulars after a replacement squad of Tigers was demolished, 24-2, by the Philadelphia A’s. Substitutes were necessary because the team went on strike to protest the suspension that teammate Ty Cobb received for beating up a belligerent heckler who, to make a bad situation worse, turned out to be disabled. The incident happened in the stands during a game in New York days earlier.

The Tigers hosted the St. Louis Browns in a split doubleheader on July 4. In the morning game, which began at 10:30, Stanage walked twice but didn’t score in Detroit’s 9-3 win. He got a breather late in the game when Jack Onslow took over behind the plate. Stanage was ready to go again for the afternoon game when the clock struck 3:30. Mullin was tabbed to start. It was the 75th time he and Stanage had formed the Tigers’ starting battery.

Mullin may have been in good spirits that day because it was his 32nd birthday, but aside from the two-hitter in DC, 1912 hadn’t been a good season for the veteran right-hander. He’d gained weight and lost his effectiveness on the mound. The Tigers waived their former ace in June, and he went unclaimed. Mullin worked on getting into better shape and earned an opportunity to continue his 11th season in a Detroit uniform. The Independence Day matchup against the Browns was only his second start since June 10.

Detroit scored single runs in each of the first three innings to give Mullin an early cushion. He helped his own cause with an RBI double in the second inning. Mullin ended up with three hits on the day. His hitting seemed to be a little sharper than his pitching that afternoon. Per the observation of Detroit Free Press scribe E.A. Batchelor (who also happened to be the game’s official scorer),

"Mullin’s lack of control was an advantage rather than a defect. (He) was just wild enough to keep the aliens guessing and hitting at bad balls. He was in a hole with almost every batter, but had nerve enough to put something on the ball when he had to get it over…Comparatively few hard fielding chances were given the Detroit fielders until late in the game. George either had the visitors striking out, flying weakly or fouling, and the balls hit on the ground…a man could play with his eyes shut."

Mullin did hit a batter, and one St. Louis runner reached safely on a Detroit error. Other than that, only two of the Browns were able to have good plate appearances against Mullin. Through the first eight innings, leadoff man Burt Shotten and sixth-place hitter Jimmy Austin had each walked twice. The Tigers’ offense, on the other hand, enjoyed a 13-hit day that included a four-run, eighth-inning rally to boost their lead to 7-0. Stanage contributed an RBI single, his only hit of the game.

There were 5,760 fans on hand at Navin Field to witness it all. In comparison, the morning contest drew 7,750 rooters. The afternoon crowd realized in the fifth inning that Mullin was working on a no-hitter. Batchelor noted,

"From that time until the finish, the twirler was cheered to the echo whenever he came to bat or finished an inning. As the game progressed, the excitement became intense and in the last two innings, the fans hardly dared breathe…You could have heard a pin drop in the big stands when the Browns came up for their last time at bat…Fans fidgeted in their seats, bit their fingernails, squirmed and chewed violently on their cigars, too excited to utter a sound."

Shotten led off the ninth by drawing his third walk of the game. Heinie Jantzen flew out to Cobb in center field for the first out. That brought up Joe Kutina. In 1911, he hit 14 home runs playing for Saginaw’s team in the (Class-C) Southern Michigan League. The vaunted Frank “Home Run” Baker of the Philadelphia A’s led the American League with just 11 that year. Mullin and Stanage were able to neutralize Kutina’s power one more time in the final frame. Batchelor reported,

"A weak foul was the best that he could do, and when Stanage picked it off (in) front of the grandstand, the pent-up enthusiasm of the fans was released in a roar like Niagara."

Del Pratt flew out to Cobb to end the game. The final score was Detroit 7, St. Louis 0. Mullin had completed the first no-hitter in Tigers history. Through it all, Stanage lent his pitcher a guiding hand from behind the plate. The man in the catcher’s mask was recognized in the next day’s Free Press game notes column. His blurb read,

"Stanage is entitled to a lot of credit for the manner in which he handled Mullin and helped him to get his no-hit game. Although Oscar must have suffered intensely in the broiling heat, he used splendid judgement, and he handled the mechanical part of his work in perfect fashion"

The Tigers and Stanage parted ways after the 1920 campaign. He caught in the minor leagues for three more seasons. Stanage returned to the Tigers as manager Ty Cobb’s pitching coach in 1925. That also gave the 42-year-old the opportunity to get behind the plate in three more games as an emergency replacement. The coaching arrangement lasted only one season.

Stanage returned to the minor leagues for one more go as a player before hanging up his tools of ignorance. Donie Bush, the Tigers’ starting shortstop in Mullin’s no-hitter, took over the managerial reins in Pittsburgh in 1927. Bush brought Stanage aboard as a coach on his first Pirates staff. Oscar actually outlasted his former teammate in the Steel City. Bush was gone by the end of 1929, and Stanage stuck with the Pirates through 1931.

Once his professional baseball days were behind him, Stanage moved back to Detroit. He stayed in shape by playing in an indoor baseball league and taking up golf. Stanage, the Tigers’ first Opening Day starting catcher at Navin Field, was one of the former Tigers who took part in Opening Day pre-game festivities in 1938, the first year that the recently expanded and newly renamed Briggs Stadium was completely enclosed. Stanage also played in the Tigers’ first Old-Timers game in June 1939.

Later in life, Stanage returned to baseball in an unusual way: game day security. In 1952, Lyall Smith from the Free Press learned that Stanage had been working as a watchman at Briggs Stadium for a couple of years. His post was at a gate leading to the upper deck. The 69-year-old former catcher told the reporter that it was a way to stay active in retirement. He’d been employed by the county clerk’s office for 21 years before retiring. Stanage thought that being a watchman was a “swell” gig because he got to watch games.

One of the games that Stanage got to see while on duty at the corner of Michigan and Trumbull that season was Virgil Trucks’ no-hitter against the Washington Senators on May 15, a 1-0 Tigers victory. No Detroit pitcher since Mullin had tossed a no-no. (Trucks went on to throw another one in New York the following month.) Joe Ginsberg was Trucks’ catcher for the masterpiece at Briggs Stadium. Since the first guy to catch a Tiger no-hitter was also in the ballpark that day, Smith had the brilliant idea to bring the two together for a conversation. Stanage told Ginsberg,

"“I know how you felt in that last inning. That ball couldn’t get in your mitt fast enough. That’s the way I felt out there in the ninth inning when Mullin got his. I almost wanted to reach up for the pitch before the batter had a chance to swing at it.”"

Ginsberg was curious about Mullin’s arsenal back on that famous Fourth of July afternoon in 1912. Stanage replied,

"“Darned if I remember. But he mostly was a fastball pitcher with a good curve. He didn’t do as much with the ball as a lot of other fellows did in those days. George used more straight stuff than most.”"

Before donning a mitt and getting into a crouch to pose for a photo with Ginsberg, Stanageidl quipped that he would’ve been fined if he had missed Mullin’s no-hitter and would’ve been fired if he had missed Trucks’. It was a unique glimpse at Tigers history for a catcher that also helped create some Tigers history.