Trouble with the Curve is the latest Replay Review, a series in which I look back at baseball/sports movies.

Trouble With the Curve is a rather clichéd sports drama stocked with stereotypes instead of characters and a fairly predictable plot; the quality of the actors involved is what carries this paper-thin story and make it even remotely watchable. This isn’t your classic sports drama, for obvious reasons, but there might be enough in there to snag a movie-loving baseball fan—or devotee of the stars involved—looking for two hours to kill.

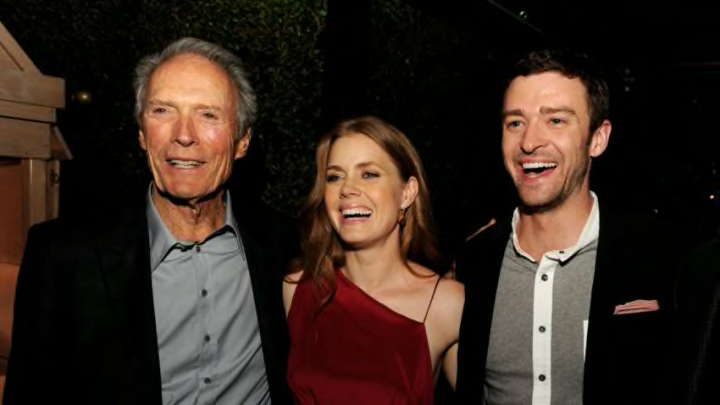

Clint Eastwood, in typically gruff form, stars as an aging Atlanta Braves baseball scout named Gus, the last of a dying breed of old school baseball men in Trouble With the Curve. Gus, a widower, has a non-existent relationship with his workaholic lawyer daughter Mickey, is being slowly pushed out of the game by villainous computer-loving front office statheads, and might be losing his eyesight as well.

The always exceptional Amy Adams gets just enough material to flex her skills as the emotionally battered Mickey, who feels compelled to postpone her own career advancement to assist her struggling father on what might be the last big scouting mission of his career. Singer-turned-actor Justin Timberlake rounds out the main cast as a washed up former Major League pitcher turned scout; once a discovery of Gus’s, Timeberlake’s Johnny is now following in his former idol’s footsteps, scouting for the Boston Red Sox. Naturally, both the aging scout and the young up-and-comer have their eye on the same prospect, a cocky slugger named Bo Gentry.

Apparently, Clint Eastwood shook off the cobwebs of retirement to return to the silver screen as a favor to the director. It’s hard to find fault in Eastwood’s performance, as he is his usual irascible self, gruff and whispery and vaguely menacing. He’s cantankerous and stubborn to a fault, seemingly unable to keep from disappointing his daughter Mickey.

Adams imbues Mickey with enough vulnerability and steel that she’s fleshed out from a thin cliché into a complex character. Unfortunately for Timberlake, he lacks the crotchety blue-collar appeal of Eastwood or the skill of Adams to overcome the shortcomings in characterization and script, leaving Johnny somewhat bland and unmemorable. In the end, Johnny is less a fully realized character than a vehicle to spur Adams’ character’s personal growth.

That’s another issue that stands out with this film. The movie is ostensibly about Gus, his failing eyesight and the looming end of his scouting career, and his distant relationship with his daughter, but it becomes quite clear that it’s Mickey who should be the central character with Gus and Johnny as supporting players. Mickey has the more compelling character journey, and is also the one who grows and changes the most. Eastwood mostly remains static; he goes up against those in the front office who think he’s losing it, but he doesn’t really need to change or grow. He was right about Gentry and is vindicated in the final scenes. There’s an opportunity in the film, if Gus were the protagonist, for the perfect climax: Gus and Mickey argue about their strained relationship, and there’s a moment where everything seems to line up. Gus can admit to Mickey he was wrong to send her away so soon after her mom died, and then later sending her off to boarding school. Gus just has to admit he was wrong—but he (and the film) can’t let him be wrong, so so the moment fades away and Gus later flees back to the Braves’ headquarters, abandoning Mickey once again.

While the movie does have its moments, overall it feels somewhat unfocused. We glimpse the bare bones of a backstory for Mickey and her prickly relationship with Gus, but it doesn’t feel properly explored, meted out in a couple of brief flashbacks and a confrontation. It turns out that the real reason Gus pushed Mickey away as a child is that he discovered a man attempting to molest her while they were on a scouting trip together. Gus stopped taking Mickey with him on his trips, choosing to send her off to relatives and later stashing her away in boarding school, leading Mickey to believe Gus didn’t want her. The movie only shallowly explores the ramifications of Gus’s impulsive decision to push Mickey away; rather than accept responsibility for effectively abandoning her after her abuse, Gus lashes out at her and then flees, leaving Mickey to chase him down and reconcile with him.

Mickey ends up giving up her fast-moving career in law to represent a player she discovers pitching behind the motel she and Gus have been staying at, and everything ends happily. The Braves sign Mickey’s discovery, Gus walks away with his dignity, the obnoxious stats-obsessed front office member (played by Matthew Lillard) is fired, and Mickey and Johnny start a romantic relationship. The end!

It’s a pity, given the quality of the actors involved—John Goodman and Robert Patrick have small roles as front office members—that this isn’t a better movie. A focus on Mickey, rather than Gus, and the excising of the romantic subplot might have helped, but that wouldn’t have made up for the shortcomings in the story or the thinly sketched characters. (Perhaps the most dramatic thing about the movie is that the screenplay was the subject of a plagiarism lawsuit.) As it stands, Trouble With the Curve is watchable, though not necessarily memorable.

When Trouble With the Curve was released in the fall of 2012, it was touted/dismissed as the “anti-Moneyball,” as both baseball-themed movies came out at the same time and took a look at baseball front offices from different sides of the “new school vs. old school” divide. While Trouble With the Curve is a flawed movie, it has enough going for it that it’s worth at least one viewing.