As part of Black History month, we look back at past figures in Detroit Tigers history. Here, we look at Hall of Famer right-hander José Méndez, who has an interesting past in the city of Detroit.

Beyond the Detroit Tigers, the state of Michigan, as a collective for the history of Black players, has stories that go back into the late 1800s, starting with University of Michigan graduate Moses Fleetwood Walker who was one of the first African-American players to play baseball, the first being Bud Fowler. The Page Fence Giants, who played in Adrian, Michigan, were one of the top Negro teams that played without a professional league from 1895 to 1898. A book by Mitch Lutzke discusses how their path to an unofficial championship..

Back in September 2020, I wrote a piece on Humberto Fernández Perez, aka Chico Fernández, the first starting regular Latin-born player in Detroit Tigers history. Ozzie Virgil Sr. was the first Dominican player to play for the Tigers in 1958, but the history of Afro-Latin players in Detroit did not start there. It started back as early as 1909.

What Afro-Latin means

To provide some context for the term “Afro-Latin” and why it is important to explain the term, recently a sibling of mine took a DNA test and found the vast majority of our DNA comes from African countries.

My father was born in Cuba, my mother was born in Spain, and I was born in the U.S., but until recently information on my grandparents was scarce.

Back in 2016, an article by Gustavo López and Ana Gonzalez-Barrera titled “Afro-Latino: A deeply rooted identity among U.S. Hispanics” was published at the Pew Research Center. It stated:

"Until recently, most Latin American countries did not collect official statistics on ethnicity or race, especially from populations with African origins. However, a recent push for official recognition of minority groups throughout Latin America has resulted in most countries collecting race and ethnicity data on their national censuses."

This may seem heavy for a baseball post, but knowing where you come from is important. And it matters in terms of public perception. For years, people were considered Hispanic OR Black rather than Hispanic AND Black, but within the Latin community, you were viewed differently if you were light-skinned. In the same Pew article, the authors state:

"Two-thirds of Latinos (67%) say their Hispanic background is a part of their racial background. This is in contrast to the U.S. Census Bureau’s own classification of Hispanic identity – census survey forms have described “Hispanic” as an ethnic origin, not a race."

José Méndez faces the AL champs the Detroit Tigers

In 1909, the Detroit Tigers won their third consecutive AL pennant, but also lost their third straight World Series, falling to the Pittsburgh Pirates in seven games. They signed a contract to play twelve exhibition games in Cuba, starting in October.

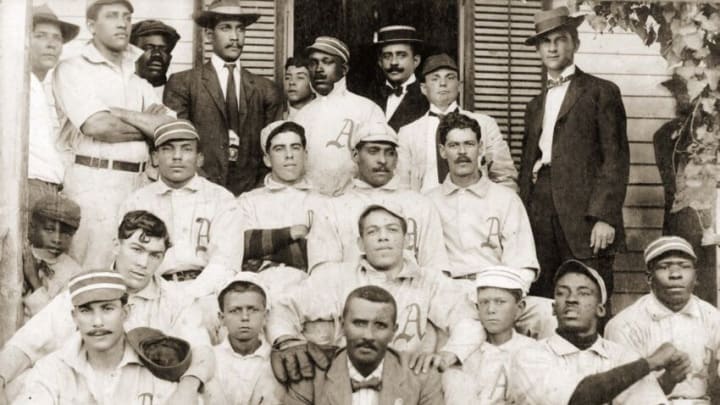

The year prior, a 20-year-old José Méndez, who by some accounts stood just 5’8 with a wiry frame, was the ace of Cuba’s Almendares Blues, later to be known as the Scorpions. In 1908, the Cincinnati Reds came to Cuba for a series of exhibitions. Méndez threw a one-hit shutout against the Reds, added six more innings of scoreless relief a few days later, and then threw another shutout after that. He had thrown 25 straight scoreless innings against a big-league club.

He would later extend that streak to 45 straight innings with 20 scoreless against a semi-pro team out of Key West, and two innings against Havana in the Cuban League. This earned Méndez the nickname “El Daimante Negro,” aka The Black Diamond.

In an article written in the 1981 Baseball Research Journal, John Holway wrote about Méndez’s run ins with the 1909 Detroit Tigers, minus Ty Cobb and Sam Crawford. He gave up 11 hits and lost his first outing 9 to 3. He fared better in his next start, allowing just one run over six innings, but his team committed four errors and the Tigers won 4-0.

In his last start against Detroit in 1909, Méndez won win 2-1 on a five-hitter, but the local paper blamed the errors Detroit committed for the loss. The Tigers lost eight games to the Blues that year. The Tigers returned to Cuba in 1910, after President Frank Navin originally said no to the idea.

It seemed Detroit wanted revenge, so this time they brought Sam Crawford, fresh off an AL-best 120-RBI season, George Mullins, who won 21 games that season, and the great Ty Cobb. Despite Crawford going 0-for-4 in their first meeting, Mullins pitched well, and the Tigers won 3-0.

Cobb did not arrive on the island until a few weeks later and, in his first clash against Méndez, he would get a hit, but then later struck out. Crawford also went 0-for-4, but the Tigers would win the series 7 to 4.

Méndez arrives in Detroit

Touring with the Cuban Stars in 1911, Méndez pitched at Mack Park (It stood at Mack Ave & Fairview) against a semi-pro team, Schmitz & Shroder (known as S&S) and shut them out 4-0. He allowed three hits and struck out nine. In 1914, after several trips to Detroit, in which he left a positive impression on the club, S&S tried to recruit Méndez to play for them.

After his time in Cuba, José Méndez played and managed the All Nations team, with players of every ethnicity and race. Formed by J. L. Wilkinson, the club included Blacks from the United States, Cubans, Hawaiians, Chinese, and a female at first base who went by the name of “Carrie Nation.” Her real name was Mae Arbaugh.

After a cup of coffee with Rube Foster’s Chicago American Giants, Méndez would settle in Detroit in 1919, the year before the Negro National League was formed.

Detroit Stars takes on the best in local semi-pro baseball

During this period, there were semi-pro teams in cities across Michigan. Along with that, a few teams came out of the Detroit car manufacturing scene, the Detroit Amateur Baseball Federation, and even the grocery giant Kroger had a team. Names like the Highland Park Merchants, the Maxwells, and the Toledo Rail Lights were all commonplace.

Even the downriver Michigan city of Wyandotte had a team that could book the Detroit Stars for the opening of their new ballpark, Corrigan Field, in May 1919.

Whatever team it was, the Detroit Stars would play. Méndez, along with Negro League great John Donaldson, not only pitched, but played in the field too, with Méndez at short and Donaldson in centerfield. Méndez, who was 34 years old when he joined the Stars, pitched in seven games, four of which he started, and posted a team-leading ERA of 2.14 in 46 innings of work.

After the season, he played winter ball in Los Angeles, and Wilkinson asked him to manage the Kansas City Monarchs in the new Negro National League. Méndez won back-to-back pennants in 1923 and 1924, and was the first manager to win the first ever modern black World Series in ’24.

History Lesson concluded

José Colmenar del Valle Méndez was inducted by the Baseball Hall of Fame in 2006, becoming the first Cuban player to receive the honor. He never played in the majors because of his dark skin.

Adolfo Luque, his lighter-skinned teammate, would put up a career 48.1 bWAR after being signed in 1914. His best season was in 1923, as a Reds pitcher, when he went 27-8 and posted an ERA of 1.93. The “Pride of Havana” would win two World Series in his time in the majors.

José Méndez made an impression on all who played against him or played for him. Hall of Famer John McGraw spoke of highly of him and called him the “Black Christy Mathewson,” one of the greatest National League pitchers ever to play the game. Tigers players were aware of how good his curveball was. Everyone in baseball who traveled to Cuba knew how good he and his fellow Cubans were. They were so good that, after 1911, major league teams wouldn’t play in Cuba again for another eight years.

While his time in Detroit was just one season for the Stars, he was one of the earliest legends to play here. That should be worth noting whether he was a Tiger or not. I am beyond grateful that the Detroit Tigers celebrate the Detroit Stars’ legacy. As we learn new information all the time, it is important to celebrate these stories.

Méndez was identified as black, but his identify goes further than that. He was not just an early folk hero in Cuba, but a talented player who could win wherever he went. He played here, in the Paris of the West, as it was known. As someone who continues to search for parts of history of my family and stories of others who look like me, I think that is pretty damn cool.

(Thanks to Patrick Ellington Jr. of the publication Guardians Baseball Insider and of Pitcher List for helping me with notes, and a big thanks to the crew over at my local SABR chapter of Southern Michigan for their help in the research of Mendez, including Gary Gillette, the co-founder & chair of the Board of Directors for the Friends of the Historic Hamtramck Stadium who assisted me in making sure my information was correct)