In the spirit of Motor City Bengals’ first annual Prospect Week, this is a story about the farm system from a bygone era. Before becoming Detroit Tigers, some key prospects used to play for a rookie league team called the Bristol Tigers.

Minor league baseball will be played again in 2021, but the landscape won’t be the same as it was before a COVID-induced shutdown wiped out the 2020 season. The Appalachian League, which had existed as a short-season rookie league since 1957, didn’t survive the recent gutting and restructuring of the minor leagues that was orchestrated by Major League Baseball. Instead, it has been converted to a collegiate summer league. Although the league lost its minor league status, its ties to Detroit Tigers history can’t be severed. Between 1969 and 1994, a number of notable prospects made their professional debuts with the Bristol Tigers, Detroit’s Appalachian League affiliate.

The Early Days

When the Detroit organization set up shop in in Bristol, Virginia in 1969, the town hadn’t fielded a pro ball team team since 1955. (Bristol’s history in the minors dates back to 1911.) Bill Lajoie, a recent hire in the Tigers’ scouting department, was given the additional task of managing the inaugural Bristol Tigers. That arrangement didn’t last past the season, and Lajoie turned his full attention to scouting. Bristol finished 34-34 with him at the helm. Lajoie and Dallas Green of the Pulaski Phillies (who went on to manage in the big leagues for 10 seasons) were named co-Managers of the Year. Glancing at the team’s roster, the one name that jumps out is Howard Johnson, but the HoJo of 1969 is not the one that played for the Tigers and Mets in the 1980s. None of the ’69 Bristol Tigers made it to the majors.

Detroit had high hopes for shortstop Tom Veryzer, the team’s first round pick (11th overall) in June 1971. Local fans were likely disappointed when the Tigers passed on left-handed pitcher Frank Tanana, who was from Detroit Catholic Central High School. Years later, Tanana confirmed that the Tigers knew about an arm injury he incurred while pitching in a high school championship game at Tiger Stadium. The Angels, who didn’t know, snapped him up two picks after the Tigers took Veryzer. For a period in the 1970s, before another injury changed the course of his career, Tanana was one of the best young pitchers in baseball. The Motor City would have to wait until 1985 to see its native son pitch for the Tigers.

Veryzer hit .225/.283/.385 at Bristol in 1971 but led those Tigers in runs (27) and tied for the team lead in RBI (20). He made enough of an impression to be named the Appalachian League’s co-Rookie of the Year along with Terry Whitfield of the Johnson City Yankees. Veryzer was called up to Detroit in 1973 and took over as the starting shortstop for a rebuilding Tigers team in 1975. Defensive whiz Eddie Brinkman had been dealt in order to clear the path for Veryzer. His fielding got him the job, but ultimately Veryzer’s struggles at the plate became too much for the Tigers to bear. After hitting .197/.230/.254 in 1977, he was traded away to make room for a prospect named Alan Trammell.

Another guy who debuted with Bristol in 1971 went on to make a much bigger impact with the Tigers, although it took him much longer to reach Detroit. Jim Leyland, a 26-year-old former minor league catcher, began paying his dues as a minor league manager by leading Bristol’s Tigers to a 31-35 record. It was his only season there. Apparently, one of Leyland’s most distinctive habits was already fully developed by then. Arnie Costell, who pitched for Leyland that season, told the Bristol Herald Courier in 2011,

"“He smoked a lot of cigarettes. He’d cup it in his hand, because in Bristol there wasn’t really a runway from the dugout to the clubhouse. We used to laugh because he thought he was hiding the cigarette but you could see the smoke.”"

The 1972 Bristol Tigers won the Appalachian League championship. A few of the players; third baseman Dan Meyer, shortstop Mark Wagner, second baseman Jerry Manuel, left-handed pitcher Ed Glynn, and right-handed pitcher Vern Ruhle; made it to Detroit, but long-term success there wasn’t in the cards for any of them. As one wave of prospects was stalling out at the big league level, a better wave of prospects was on its way into the farm system.

The Golden Era

Bill Lajoie, Bristol’s former manager, had been working his way up in the Tigers organization. By 1974, he’d been promoted to scouting coordinator. The next year, he became director of player procurement. That title had long been by Ed Katalinas, who was best known as the scout who signed Al Kaline. The June 1974 draft presented Lajoie with his first big opportunity to start shaping the future of the Tigers. He shared his philosophies about finding players who could succeed in MLB with writer Anup Sinha years later when they collaborated on a book called Character Is Not a Statistic: The Legacy and Wisdom of Baseball’s Godfather Scout Bill Lajoie.

Taking the advice of one of his scouts, Jack Deutsch, Lajoie went to California to watch a player named Lance Parrish. The 6’3″ youngster was a catcher who also a pitcher and a third baseman. Parrish was an excellent athlete all the way around. On the basketball court, he was a forward and a guard. On the football field, he saw action as a quarterback and a defensive back. He also signed a letter of intent to play football at UCLA. It didn’t take long for Lajoie to decide that he wanted to draft Parrish in the first round. He got his man with the 16th pick overall. Parrish said,

"“I was hoping I’d go that early. I thought I might have been picked earlier by the Phillies or the Angels. I was a little surprised to be drafted by Detroit. I might have talked to a Detroit scout this year, but I never worked out with them. I worked out with six clubs and twice with the Angels at Anaheim Stadium.”"

Newspapers’ draft coverage had Parrish listed as both a catcher and an infielder. He didn’t spend any time behind the plate in Bristol in 1974. He played 55 games at third base and even made 15 appearances in the outfield. Parrish’s defense was rough. He made 20 errors as a third baseman, and his fielding percentage was .844. The conversion back to catching began the following year. Only Bill Freehan (1,581) and Oscar Stanage (1,072) caught more games in a Detroit uniform than Lance (1,039). No other Tigers catcher has made it to 1,000. For Bristol’s Tigers, Parrish hit .213/.301/.395 in 290 plate appearances and led the Appalachian League in strikeouts with 92. The guy who would someday be known as “The Big Wheel” also led the team with 11 homers. Parrish’s 212 home runs as a Detroit Tiger are ninth most in franchise history.

One of Bristol’s pitchers was unheralded in 1974, but the spotlight would find him a couple years later. Mark Fidrych, a kinetic Massachusetts kid, was the Tigers’ 10th round pick in the draft that netted Parrish. Fidrych was a strictly a reliever in Bristol and pitched effectively. In 34 innings (23 appearances), he had a 2.38 ERA, a 1.176 WHIP, and struck out 10.6 batters per nine innings. He scooped up three wins in relief and was credited with seven saves. Strangely, there is newspaper coverage that referred to him as “Steve” Fidrych. His middle name was Steven. Mark picked up another name during his stay in Bristol. It was Jeff Hogan, a coach on the team, who christened “The Bird” with his famous nickname. The story of Fidrych’s season in Bristol is wonderfully told in the second chapter of Doug Wilson’s book The Bird: The Life and Legacy of Mark Fidrych.

Parrish, Fidrych, and their Bristol teammates, including future Tiger Tim Corcoran won the Appalachian League championship in 1974. No Bristol team ever came close to touching their 52-17 record. The pitching staff was led by left-hander Bob Sykes, the Tigers’ 19th round pick that year. In 13 starts (seven completed), he logged 101 innings. He finished with a sparkling 11-0 record, 1.07 ERA, and 0.822 WHIP. Sykes struck out 96 and walked 31. He was one of the most dominant pitchers in the league that season, but Sykes’ greatest value to the Tigers was as a trade chip. In December 1978, he was part of a deal that brought shutdown reliever Aurelio Lopez to Detroit.

Lajoie found a diamond in the rough in the fifth round of the June 1975 draft. Lou Whitaker, a third baseman from rural Virginia, was assigned to Bristol. In 141 plate appearances, he hit .237/.369/.333, but he drew 25 walks and struck out only 13 times. That good hitter’s eye stayed with him long after he moved on from Bristol. Whitaker finished his 19-year big league career with more walks (1,197) than strikeouts (1,099). Defensively, he showed off the attributes that had landed him on Detroit’s radar. In 110 chances at the hot corner for the Bristol Tigers, Whitaker had 34 putouts and 67 assists while making only nine errors. In the Lajoie book, Sinha wrote,

"“…He was a smooth-as-silk fielder with a well-above average throwing arm…Whitaker was a good runner who played the game hard and had instincts both with the bat and glove.”"

Did you know that there is an Appalachian League Hall of Fame? Whitaker was inducted in 2020. The first class of inductees, in 2019, included Whitaker’s long-time double play partner Alan Trammell.

In June 1976, Trammell was Detroit’s second round pick. For the second time in three years, the Tigers snatched an athlete away from UCLA. Trammell had signed a letter of intent to play baseball for the Bruins. An excellent shortstop from the beginning, he was projected to be a major leaguer even if the bat didn’t develop too much. The comparisons were shortstops like former Tiger Eddie Brinkman or the Orioles’ Mark Belanger, both weak-hitting Gold Glove winners. Brinkman, a career .224 hitter, played in over 1,800 games. Belanger, who was still active in ’76, finished with an average of .228 in just over 2,000 games. Trammell surpassed them both. The future Hall of Famer hit .285 in over 2,200 games and had a monster season in 1987 (.343/.402/.551 with a 155 OPS+, 205 hits, 34 doubles, 28 HR, 105 RBI, and 329 total bases).

After 41 games in Bristol, Trammell was slashing .271/.386/.314 when something unexpected happened. The 18-year-old was bumped up to Double A Montgomery after Rebels shortstop Glenn Gulliver was injured. It was an aggressive promotion. There weren’t a lot of teenagers in the Southern League. However, at Single A Lakeland, the team managed by Jim Leyland was in the hunt for the Florida State League title. Instead of disrupting them, the call for help went to Detroit’s rookie league team in Bristol. Understandably, Trammell didn’t hit nearly as well in Montgomery against older and more experienced pitchers, but he got his first taste of postseason baseball there. Trammell remained in Double A for the rest of the season, and the Rebels went on to win the Southern League championship.

Trammell and Whitaker became teammates in 1976. In the regular season, “Sweet Lou” was part of Leyland’s Lakeland team, who went on to win the FSL title. Whitaker, the league’s MVP, was a key reason why. In the fall, the two players were paired together for the first time on the Tigers’ Florida Instructional League squad. Whitaker was shifted over to second base and clicked with Trammell right away. Near the end of the 1977 season, the newly-formed double play duo arrived in the majors to stay.

One of the four players in Lajoie’s 1976 draft class who went on to successful big league careers was right-handed pitcher Dan Petry. Detroit’s fourth round pick was assigned to Bristol for his first taste of pro ball. Petry led the Appy League Tigers’ staff with 14 starts. He finished 2-3 with a 3.76 ERA and 1.392 WHIP. That was pretty respectable for the youngest pitcher on the team. In the magnificent 1984 season, the 18-8 Petry led Detroit’s staff in ERA (3.24), ERA+ (121), WHIP (1.273), shutouts (2), and bWAR (3.5). Scout Dick Wiencek brought Petry and Trammell, a pair of Californians, to Lajoie’s attention. Petry reminded Wiencek of a pitcher he’d signed years earlier while working for the Twins. The veteran scout remarked,

"“I think Petry is awfully similar to Bert Blyleven when he signed. Dan is 17 like Bert was, and he has the same kind of stuff at this stage. Of course, Bert came along fine and is one of the leading pitchers, but you never know about these deals. With proper development, we think Petry can be a major league pitcher.”"

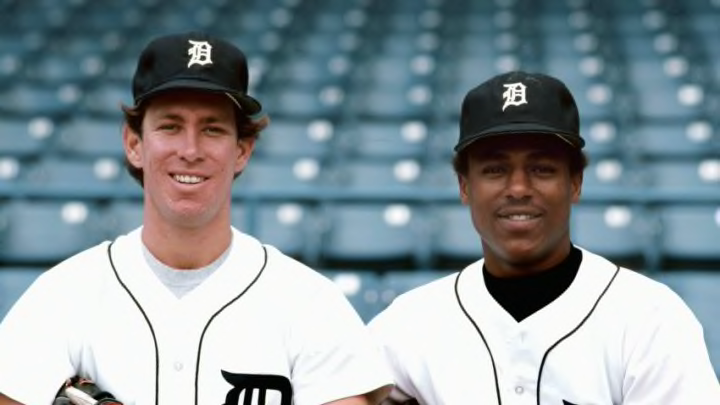

Fellow Bristol alumni Parrish, Whitaker, and Trammell were already entrenched in the Tigers starting lineup when Petry made his major league debut in 1979. The four of them were part of the nucleus of the team that won the World Series in 1984. That season was the most exciting that Tigers fans had experienced since the “Year of the Bird”. Fidrych, the former Bristol hurler, captivated the world in 1976. The three-year period when all of those players made the jump from high school to the pros was a golden era of Bristol baseball.

The Next Generation

After that group moved on, it was quite some time before Bristol saw any prospects who later became key contributors in Detroit. Milt Cuyler, the second round draft pick in 1986, stole 52 bases as a Tigers rookie in 1991 (fifth most in the American League) and finished third in AL Rookie of the Year voting. He wasn’t able to stick as a full-time player, though. Surprisingly, Cuyler wasn’t that much of a speedster in Bristol. He stole 12 bases for those Tigers in ’86 and finished fourth on the team. Cuyler cracked Baseball America‘s top ten Tigers prospect rankings in 1988 and was ranked as high as number four in 1989.

Shortstop Travis Fryman was the best prospect to come through Bristol since Alan Trammell in 1976. In the first round of the June 1987 draft, the Tigers selected him with a supplemental pick (30th overall) that they received for losing Lance Parrish to free agency. After Fryman signed, Detroit scouting supervisor Jax Robertson said,

"“I feel Travis will spend the whole summer there (in Bristol), but we look for quick advancement from him. We had five different people see him and there’s no doubt in my mind that Travis can play shortstop in the big leagues right now. That may sound like an overstatement, but he’s got that kind of talent.Offensively, he needs some work and he knows that. But he’s got good hand-eye coordination and bat control, and that shouldn’t be a problem. He will advance in the organization as he hits.”"

Fryman led the Bristol Tigers with nine doubles and hit .234/.297/.294 overall in 1987, but the team stumbled to a 20-49 record, worst in the Appalachian League. Baseball America ranked Fryman ninth in the Tigers farm system in 1988. He rose to number two in 1990, the year he was called up to Detroit. Fryman thrilled fans at Tiger Stadium with a three-run home run in his second big league game. It was his first hit, and it soared over the 400-foot mark in center field, near the ballpark’s flagpole.

Beginning at Bristol, Fryman had been groomed to become the Tigers’ shortstop of the future. He played there and at third base for three of his first four years in the majors. He wasn’t a third baseman at all in the minors. After a broken right ankle ended Trammell’s season in May 1992, Fryman became the everyday shortstop. He was the full-time third baseman during his last four years in Detroit. Fryman was a productive player in a down era for the franchise. His best season was 1993, which was the last season the Tigers fielded a team with a winning record until 2006. In eight seasons, he hit .274/.336/.779 with a 106 OPS+, accumulated 27.5 bWAR, and made four All-Star teams as a Tiger. Fryman had a couple good seasons left after being traded away, including his only Gold Glove season.

Signing Tony Clark seemed like it might be a tall order. Not just because he was 6’8″. The Tigers’ first round pick in 1990 (second overall, one behind future Hall of Famer Chipper Jones) had signed a letter of intent to play basketball at the University of Arizona. Clark wanted to play minor league baseball and college hoops. Detroit wanted the big switch-hitter enough to let him do it. John Lowe of the Detroit Free Press reported that Clark’s $500,000 signing bonus wouldn’t be reimbursed if he got hurt playing basketball. At the time, it was the largest bonus given to a high school draftee. Dick Wiencek, who had become the Tigers’ director of Western States scouting, explained the Tigers’ perspective. He said,

"“Any time you allow someone to play basketball, there is a risk. It’s the kind of gamble that was worth taking. If he does make it, he’s an impact player who can drive in runs and put people in the park.If Tony progresses, we hope to have someone like Darryl Strawberry. Almost everybody in the organization, including Bill Lajoie, the general manager, saw him play. We had a consensus of opinion that this was the right guy for the Tigers.”"

The Appalachian League season was well underway when Clark arrived in Bristol. He only got into 25 games with those Tigers, who played him in the outfield. In mid-August, with the season still in progress, Clark left the team. It was time to switch from the base to the basket. Just before he departed for Arizona, he hit his only home run in a Bristol uniform. Joe McDonald, Tigers vice president of player procurement and development told the Free Press that the organization liked the swing and the power that Clark showed in batting practice, but acknowledged that he was “playing catch-up” when it came to game action. Baseball America ranked Clark as the Tigers’ eighth best prospect in 1991.

Clark then disappeared from the rankings until 1994. His athletic career had undergone some dramatic changes. In December 1990, he left Arizona and enrolled at San Diego State University. The transfer wiped out his eligibility for the rest of the season. In June 1991, just before Clark would’ve begun his second baseball season, it was revealed that he’d suffered a back injury while playing basketball. He didn’t play baseball that year. Clark finally reached Detroit in 1995 after climbing to the top of Baseball America’s top ten Tigers prospects list. He took over the first-base job the following season when Cecil Fielder was traded. Clark, whose years with the team spanned the closing of Tiger Stadium and the opening of Comerica Park, hit 156 of 251 HR big league home runs for the Tigers.

In the final years that Bristol was a Tigers affiliate, future major leaguers Danny Bautista (1990), Jose Lima (1990), Justin Thompson (1991), Trever Miller (1991), Frank Catalanotto (1992-93), and Juan Encarnacion (1994) passed through town. After the 1994 season, the Detroit organization left Bristol and moved its short-season rookie team to the Gulf Coast League. Bristol became affiliated with the White Sox, who fielded a team there through 2013. The Pirates took over the following season, and Bristol remained with that organization until the recent reclassifications stripped the Appalachian League of its minor league status.